Saturday, 30 April 2011

Portal 2 and Computer Games as Art

Posted by

Jon Stone

Although I've had a deeper-than-average affection for computer games for many years now, my commitment to poetry still runs deeper. How can I tell? Well, apart from the fact that I gave up designing Duke Nukem 3D levels and Klik n' Play games and started writing poems, there's the debates within each medium's respective communities. I feel compelled to get stuck into the wranglings regarding prize culture, mainstream/non-mainstream poetry, publishing, audience expansion etc. You can see how worked up I get about those things right here on this blog. I feel that stuff is important.

The kind of arguments that crop up around gaming, however, more often than not just leave me baffled and disillusioned, images of petulant, whiny geeks swimming around in my head. Take Portal 2, which, as far as I'm concerned, is the latest surefooted step towards making interactive storytelling the artform of the future, as well as (along with its predecessor) a significant stride away from games as a primarily male-orientated, borderline mysogynistic medium. I'll be fair and say that most of the thick-as-pigshit responses to Joe McNeilly's feminist reading of the original Portal (sample: "And since when the fucking hell have guns been phallus-like?") are far from representative of the gaming community. In fact, I would say that the eagerness, both on a popular and critical level, to embrace both games comes not only from an appreciation of their technical qualities but also from a genuine hunger to move in a socially inclusive direction. Gaming, just like poetry, is at war with a debillitating image of itself. Just as poets are loser musos fortifying university literary departments, gamers are overweight single men trapped in dark boudoirs. Normal people in both groups face the double antagonism of lazy stereotyping from outsiders and mutated forms of macho posturing in their own camp (for poets, it comes in a variety of forms; for gamers, it's usually Mr "Game is too short and easy - I finished it in forty minutes while replaying Half-Life 2 with my other hand".)

Nevertheless, I find myself asking: what do Portal 2 players think they're achieving by complaining that they have to pay extra if they want to unlock virtual comedy hats for the robots? Or by whining that the PC version might have been developed as a port of the console versions? In their droves, by the way - so much so that gaming blog RockPaperShotgun felt compelled to post a careful refutation of the various petty accusations that have been levelled against the game. I've tried, with little success, to understand exactly what the problem is with selling people downloadable extras on top of the original game. Supposedly, it's 'immoral', it's evidence of the developers not working hard enough for their money, it's time they could have spent making the main product more watertight and so on. Really, though, I think it comes down to this: many gamers are rampant completists and their dealer keeps raising the price of their addiction. They don't want to pay $5 for a silly hat but feel bizarrely compelled to.

There is an argument that modern games, which have replaced high score tables with percentage complete bars, lists of achievements to tick off and unlockable extras, encourage a completist attitude. But really they're just giving old schoolers a nicotine patch to help them cope with the transition from games as contests of skill, with empirical or quantitative measures of success, to a medium-cum-artform that seeks to satisfy and enrich emotionally and intellectually, non-quantifiably. Particularly in a country like Britain, where the arts are increasingly asked to come up with figures to prove their cultural value, it's a real positive that mainstream games which sell in their millions are being pushed in this direction.

In Portal 2, none of the suite of pleasures I took from playing through were as a result of my own proficiency and game-playing competence. In fact, one of the reasons I rarely got annoyed with the game is that it's built with the idea of constant learning and progression in mind, rather than forcing you to repeat the same tasks again and again until your fingers learn the right twitch patterns. I enjoyed cracking the puzzles because the results involved devious manipulations of space and physics, as well as defeating lethal turret guns with nothing more harmful than holes in the ground and blue paint. The game tests you intellectually without demanding you develop yet another non-transferable expertise, and rewards a furrowed brow with the kind of entertainment that delights the grown-up child in any of us. It teaches you to think laterally, and to meet force and apparent gross unfairness (as well as misuse of power) with cunning thought and resourcefulness.

I also enjoyed that rarity in interative narration - a story with plenty of twists and turns that never feels like it's trying to tell you to be serious and stop mucking about. Whereas in a game like Halo 3, the most fun I had was at the developers' expense - by bludgeoning soldiers who were supposed to be on my side and watching them consistently react as if it was an unfortunate accident - Portal 2 marries up the player's aims with the protagonist's so successfully that you genuinely want to do what's expected of you: solve the puzzles, upset the gun turrets and break out of the facility. There are parts where I would have wanted to drive a harder bargain with either of the neurotic AIs that partner up with you, but they were never less than useful to have along.

The story is also extremely witty. I'd go so far as to say it borders on Vonnegutian. Portal 2's dialogue and visual black comedy shows up nearly every other future sci-fi dystopia game I've played as the humourless, intellectually arid bag of cliches it really is. It's the kind of game you want to play with other people just so you can share the most beautifully scripted (and voiced) moments.

Talking of playing with other people, I haven't had the chance to start the co-op mode yet, which lets you and a friend solve test chambers together. If games can continue in this direction, it will draw a line under the stereotype of the antisocial bedroom dweller forever. It's not hard (although rather painful) to imagine this sort of technology being used to train employees in basic trust and collaboration skills.

The computer games as art debate is well rehearsed; as sympathetic as I am to the medium, most of the arguments in favour of its acceptance as an artform could be applied to, well, football or gardening, ie. it's immensely inspiring and gratifying to see an intricate thing done spectacularly well. That's all very well, but we still need the kind of high art that provides the fuel for break-out thinking and grass-roots solutions to social problems that politics avoids addressing. Based on the general behaviour of gamers that I've come across, we're not there yet, but there's certainly hope. And that's of interest to poets to because computer games might be our last, best hope of maintaining an awareness of and connection to art within the disenfranchised, systematically betrayed and aggressively consumerfied generations currently growing up.

No Furniture So Charming retrospective

Posted by

Unknown

So shortly before dashing off to Holland, Jon and me took part in the London Word Festival event 'No Furniture So Charming', an evening of speculation on the idea of the future library (see post below).

NFSC was a well organised and attended event, held upstairs at the Bethnal Green Library (which is a lovely library. Do visit it - good poetry section) and organised into bouts of quickfire microlectures, interspersed with panel discussions by prominent information professionals.

The strict five minute talk-time rule was enforced by loudly stamping a book and shushing any overrunning speaker, an idea I wasn't that keen on. Sure, a schedule is a schedule, but there's something uncomfortable about an entire room ganging up on a lone individual, and the first speaker didn't get to finish his sentence before being sent offstage. One audience member liked it even less than me, though. An information professional himself, he was very vocal about his 'disgust' at these reinforced stereotypes of librarians as shushers and stampers, and the naive fetishism of the book in the speeches he'd seen. He made some interesting points and it's good to see passion for a subject, especially one under threat. Certainly a spot of controversy can keep things spicy, and host Travis Elborough addressed the situation well.

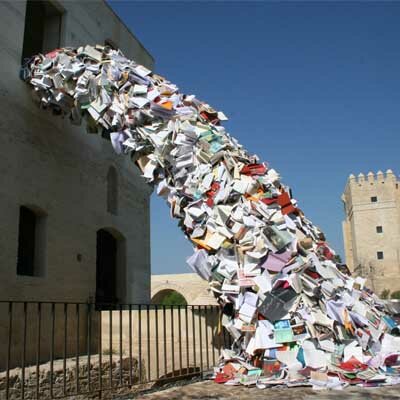

Anyway, onto the main entertainment. The speeches themselves were varied and many had intriguing takes on the subject, ranging from Nicky Kirk's revamping of the actual architectural layout of the future library into a cathedral of learning, complete with soundproofing and annexed areas for different purposes, to the value and potential of mobile libraries, to nerdy passion for books in general.

Our presentation was a short text adventure, designed to illustrate in a lighthearted way the potential for a the beginnings of a virtual library, kicking off, as computer games have, with a simple format, something to build on in order to create whole worlds unrestricted by space, social limits or physics. Although tongue-in-cheek, we wanted to address the point that pure nostalgia will not save even the most beloved of physical buildings from the financial axe, and perhaps it is wise to make contingency plans.

One of the most interesting microlectures was Rachel Coldicutt's piece on the joy to be found in being denied the exact thing you seek, and the resulting ricochet effect that can lead you to happen upon something even more interesting. In an age where almost everything is speedily accessible online, her idea of restriction as an inspirational force, almost like a strict poetic form determining your choices and making you expand your phraseology, is an appealing one.

The panel were invaluable to keeping the event focused on the issues facing the sector at the moment - where we as members of the public can romanticise and guess at the use and value of libraries, having professionals present who can quote relevant statistics and give clear examples of usage patterns helps to rein in the pure adoration for books, which, though vital to the survival of libraries, will not cut it when facing off against a government with money on the brain. Perhaps if the event is repeated next year, more librarians as presenters would be good.

The most reassuring thing to emerge from 'No Furniture So Charming' is the knowledge that this is still such a complex issue, with so much debate surrounding the actual role libraries are, or should be adopting, that marketing men and those wishing to privatise, rebrand and commercialise public libraries wouldn't have a clue where to start.

***

London Word Festival is still going on! Check out the other treats on offer at www.londonwordfestival.com

Labels:

events

Thursday, 21 April 2011

London Word Festival: No Furniture So Charming

Posted by

Jon Stone

Thu 21 Apr

No Furniture So Charming

Philip Jones, Nora Daly, Chris Meade, Charles Holland, Jon Stone & Kirsty Irving, Peter Law, Dan Thompson, Trenton Oldfield, Tom Armitage, Nicky Kirk, Rachel Coldicutt & Ruth Beale

hosted by Travis Elborough

Bethnal Green Library | 7pm | £5 adv/£7 doorA night devoted to the architecture of knowledge and the future of book-borrowing. Much more than just bricks and mortar, the public lending library has long been considered the cornerstone of an educated and literate population, but what lies ahead for the future?

Borrowing its title from Sidney Smith’s description of books, No Furniture So Charming gathers artists, writers, creatives, technologists and architects to present their vision for the library of the future. Be it a personal utopia, a visionary work of science fiction, a digital or practical re-imagining of user centred design or a call to action.

A crack panel of hardback, paperback and e-book judges will discuss and debate the merits of each idea as they pay homage to a revered space in times of change.

--

(Kirsty and I are presenting a library text adventure. Then we're going on holiday for a week. Argh!)

Labels:

events

Monday, 18 April 2011

100 Word Review - The very idea of a 28 year old collecting transmogrifying robot toys

Posted by

Jon Stone

I get very bored of the dull-edged quips about Transformers. We all know it's a shallow 80s marketing wheeze turned banal film trilogy. But among the more simple pleasures in life, collecting these increasingly sophisticated action figures rates highly for me, tainted not by embarrassment but the sad probability of sweatshop labour being employed at some point. They're not all thugs either. Perceptor here is a scientist – look, he's checking his chronometer. And the franchise has been so well treated by various writers (including Brits Simon Furman and Nick Roche) that it's easy to love some of these characters.

Saturday, 16 April 2011

Birdbook: Here at last!

Posted by

Jon Stone

I wanted to put up a photo of the 23 boxes of Birdbooks currently stacked in

Labels:

Sidekick Books

Friday, 15 April 2011

100 Word Review - 100 Word Reviews

Posted by

Jon Stone

Aside from the fact that 100 words is all the average person should need in order to sum up their opinions on most subjects, the appeal of this form lies in its rejection of specialism. One of the big grumbles about our generation is that our knowledge is broad and shallow. But to make oneself an expert is also a kind of retreat, a taking up of a fixed, unshakeable viewpoint, and generally not even a feasible option for most people. So let's celebrate the overview, which permits us to inspect objects lightly and to trace the distances between them.

Labels:

100-word reviews

Wednesday, 13 April 2011

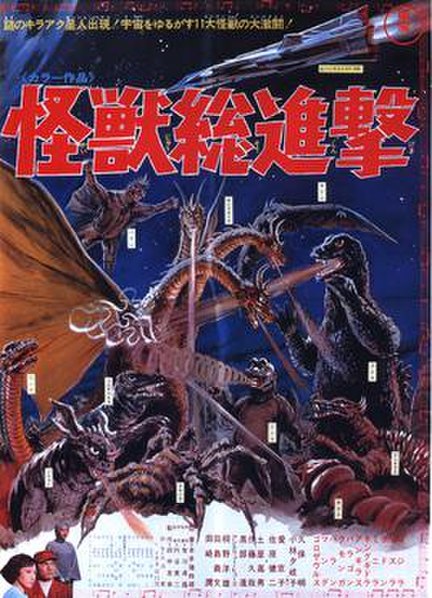

100 Word Review - Destroy All Monsters

Posted by

Jon Stone

Often cited as one of the best Godzilla films, Destroy All Monsters combines the unintentionally hilarious antics of a yellow-suited gang of astronauts with occasional clips of Toho monsters trashing familiar landmarks. It's barmy premise involves all the monsters of earth being rounded up to live on an island, their being brainwashed to attack mankind and then banding together again to dogpile King Ghidorah in the finale. As absolute nonsense goes, it works surprisingly well; the major disappointment is the small parts afforded to most of the rubber-suited rum'ns, with most only granted brief cameos and some not even namechecked.

Labels:

100-word reviews,

film

Tuesday, 12 April 2011

Guest-blogging at the Hate-Mongering Tart

Posted by

Jon Stone

Throughout April, Emily Kristin Anderson's blog, The Hate-Mongering Tart, is inviting a host of poets and poetry types to guest-blog on various subjects.

Here's Kirsty on writing a poem a day for the month.

And here's me on collaborative poetry collection.

Here's Kirsty on writing a poem a day for the month.

And here's me on collaborative poetry collection.

Monday, 11 April 2011

Traffic Both Ways 1

Posted by

Jon Stone

"Accessibility is a term I consider appropriate for discussion of supermarket aisles, library shelves, and public lavatories. It is not a word I consider relevant to the discussion of poetry."

Geoffrey Hill

"Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people."

Adrian Mitchell

The above quotes (apologies for reproducing the Mitchell one for the zillionth time) represent the polar ends of one of those debates that don't seem to progress at all over the course of one's lifetime. The question is thus: does contemporary poetry need to be more accessible? Is it exclusive and elitist (Mitchell's implication), or is too much of it already dumbed down (Hill's)?

Seems a harmless enough question to play with, starting with what we mean by 'accessible', but somehow it's become a war of attrition, with theoretical villains, victims and saviours getting thrown around left, right and centre. When London poetry night Bang Said the Gun promotes itself as 'poetry for those who don't like poetry' (or, more recently 'poetry not ponce') it's riffing off the image of the serious poet as a snob and killjoy. Such is the gamut that runs from populism to obscurity, however, that that Bang crowd's ponce directs his own misgivings not back towards no-frills performance poetry but his very own notion of the ponce. Here's Simon Armitage's famous anti-avant provocation:

Hill, here, is the ultimate ponce, the ponce's ponce. Bang are (again, for the purposes of this illustration) the knuckle-draggers - that area of poetry rarely directly criticised for fear of drawing attention to it but glanced at sideways whenever some esteemed character makes a withering remark about doggerel. Armitage is both, depending on which camp you're in. The victims, meanwhile - again, depending on your camp - are either the poor commoner whom pretentious poets deliberately exclude through wilful obfuscation, or the unsung geniuses who die in poverty because our feeble-hearted modern world thrives on banality and spits on innovation.

The whole exchange is just as often roundly dismissed by those taking a broader view of poetry. In this extract from Beautiful & Pointless, David Orr sums up the situation facing all sides of the debate:

Performance poetry promotors may retort that their approach breaks the cycle, but let's be realistic - the crowd at such an event are, more often than not, laughing at the jokes and enjoying the spectacle, and are just as indifferent or otherwise to the poetry as they would be at a TS Eliot prize reading. Sugaring the pill doesn't make the drug work; it just makes it go down more easily.

In spite of this, it doesn't follow the debate should just be put on one side. I don't agree with Hill that accessibility is irrelevant to poetry and I don't like what seems to be implied from that - that poets and poetry should have carte blanche to pursue their own course without the need to check how in touch they are with broader culture. It's not good enough to just shrug at the chasm and carry on, certain that, in its own incomprehensible way, what you're doing is important.

On the other hand, the answer to the chasm isn't populism or notions of directness and simplicity. Let me be clear: I certainly share some of the frustration with some forms of experimental/avant garde/non-mainstream poetry, partly out of a sense of exclusion from (and suspicion of) the academic world, where it is more concentrated and more actively embraced, and particularly when wading through some of the attempts to explain its appeal. Here's the Guardian's Robert Potts on reading Prynne:

This is, more or less, the experience I get from reading a range of mainstream poetry, or rather, from reading generally, so what is NMS poetry offering extra besides a headache?

Here's where that line of criticism falls down though: I have read NMS poetry that I like, that has, to my eye, the quality of something skilfully done, musical and original. And the vagueness with which I can express that revelation is the real problem here, not just in regards to experimental poetry but all poetry. That is, the struggle I have with the experimental is finding the words to talk about it (see these two recent, troublesome reviews I've written for Happenstance) and it's the same struggle that faces the average reader when confronting any poetry at all. I've mentioned this in previous posts but it remains, to my mind, an extremely pertinent point: to be able to engage with poetry, to be part of its audience, one needs to be able to respond to it. And the kind of development one has to undergo in order to be able to respond to it can be a question of personal or social resources. It isn't wholly the responsibility of the individual, nor is it wholly the responsibility of poets, nor the government and its quangos, but all can (and to some extent must) play a part.

So in short: does contemporary poetry need to be more accessible? Yes. Does that mean we need to stop using big words, innovative forms and complex syntax? No.

Geoffrey Hill

"Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people."

Adrian Mitchell

The above quotes (apologies for reproducing the Mitchell one for the zillionth time) represent the polar ends of one of those debates that don't seem to progress at all over the course of one's lifetime. The question is thus: does contemporary poetry need to be more accessible? Is it exclusive and elitist (Mitchell's implication), or is too much of it already dumbed down (Hill's)?

Seems a harmless enough question to play with, starting with what we mean by 'accessible', but somehow it's become a war of attrition, with theoretical villains, victims and saviours getting thrown around left, right and centre. When London poetry night Bang Said the Gun promotes itself as 'poetry for those who don't like poetry' (or, more recently 'poetry not ponce') it's riffing off the image of the serious poet as a snob and killjoy. Such is the gamut that runs from populism to obscurity, however, that that Bang crowd's ponce directs his own misgivings not back towards no-frills performance poetry but his very own notion of the ponce. Here's Simon Armitage's famous anti-avant provocation:

"You can probably split poets into two distinct groups. There are those people who want to try and work out the chemical equation for language and pass on their experiments as poems and, very simply, on the other side there are people who want to sing songs and tell stories—and I’m with that bunch."

Hill, here, is the ultimate ponce, the ponce's ponce. Bang are (again, for the purposes of this illustration) the knuckle-draggers - that area of poetry rarely directly criticised for fear of drawing attention to it but glanced at sideways whenever some esteemed character makes a withering remark about doggerel. Armitage is both, depending on which camp you're in. The victims, meanwhile - again, depending on your camp - are either the poor commoner whom pretentious poets deliberately exclude through wilful obfuscation, or the unsung geniuses who die in poverty because our feeble-hearted modern world thrives on banality and spits on innovation.

The whole exchange is just as often roundly dismissed by those taking a broader view of poetry. In this extract from Beautiful & Pointless, David Orr sums up the situation facing all sides of the debate:

"A smart, educated person ... is often not so much annoyed by poetry as confounded by it. Such a reader doesn't look at a contemporary poem and confidently declare, "I don't like this"; he thinks, "I have no idea what this is... maybe I don't like it?" In fact, if more people actively disliked poetry, the news would be much better for poets: When we dislike something, we've at least acknowledged a basis for judgment and an interest in the outcome. What poets have faced for almost half a century, though, is a chasm between their art and the broader culture that's nearly as profound as the divide between land and sea, or sea and air. This is what Randall Jarrell had in mind when he said that "if we were in the habit of reading poets their obscurity would not matter; and, once we are out of the habit, their clarity does not help." The sweetest songs of the dolphins are lost on the gannets."

Performance poetry promotors may retort that their approach breaks the cycle, but let's be realistic - the crowd at such an event are, more often than not, laughing at the jokes and enjoying the spectacle, and are just as indifferent or otherwise to the poetry as they would be at a TS Eliot prize reading. Sugaring the pill doesn't make the drug work; it just makes it go down more easily.

In spite of this, it doesn't follow the debate should just be put on one side. I don't agree with Hill that accessibility is irrelevant to poetry and I don't like what seems to be implied from that - that poets and poetry should have carte blanche to pursue their own course without the need to check how in touch they are with broader culture. It's not good enough to just shrug at the chasm and carry on, certain that, in its own incomprehensible way, what you're doing is important.

On the other hand, the answer to the chasm isn't populism or notions of directness and simplicity. Let me be clear: I certainly share some of the frustration with some forms of experimental/avant garde/non-mainstream poetry, partly out of a sense of exclusion from (and suspicion of) the academic world, where it is more concentrated and more actively embraced, and particularly when wading through some of the attempts to explain its appeal. Here's the Guardian's Robert Potts on reading Prynne:

"Part of the pleasure for some readers, including myself, is the discovery of fresh vantage points on the world, garnered from chasing references in the poems, whether historical, musical, literary, scientific or economic. As one reader has said, 'the experience I always get reading Prynne, going to the dictionary and the encyclopedia, is the excitement I was cheated out of by my education, having it all served up, rather than, like my grandfather, finding it out for myself (after work) with great effort and little societal encouragement.'"

This is, more or less, the experience I get from reading a range of mainstream poetry, or rather, from reading generally, so what is NMS poetry offering extra besides a headache?

Here's where that line of criticism falls down though: I have read NMS poetry that I like, that has, to my eye, the quality of something skilfully done, musical and original. And the vagueness with which I can express that revelation is the real problem here, not just in regards to experimental poetry but all poetry. That is, the struggle I have with the experimental is finding the words to talk about it (see these two recent, troublesome reviews I've written for Happenstance) and it's the same struggle that faces the average reader when confronting any poetry at all. I've mentioned this in previous posts but it remains, to my mind, an extremely pertinent point: to be able to engage with poetry, to be part of its audience, one needs to be able to respond to it. And the kind of development one has to undergo in order to be able to respond to it can be a question of personal or social resources. It isn't wholly the responsibility of the individual, nor is it wholly the responsibility of poets, nor the government and its quangos, but all can (and to some extent must) play a part.

So in short: does contemporary poetry need to be more accessible? Yes. Does that mean we need to stop using big words, innovative forms and complex syntax? No.

100 Word Review - Transformers: War for Cybertron (PC)

Posted by

Jon Stone

Transformers disappoints in yet another medium. If most games are a series of repetitive actions masked by a veneer of original spectacle and narrative purpose, then at best, TF: WFC needs a slicker veneer, since it soon sinks in that all you're doing is following an arrow and shooting down the same four enemies. The transforming gimmick is wasted – cars either handle exactly like robots or nitro-blast forward uncontrollably. The range of familiar characters is sparse and all are very much alike (Bumblebee doesn't spy; he slaughters), while the constant reliance on ammo-respawn points near bosses is woeful design.

Labels:

100-word reviews,

games

Sunday, 10 April 2011

100 Word Review: It's Your Write event (V&A Museum of Childhood)

Posted by

Unknown

Both an exercise in childhood reminiscence (cutting and binding at a table with strangers) and a sharp reminder of how ludicrously talented the world is, this colourful, lively, free celebration of the hand-made, the self-published and the reassuringly independent was fantastic. Zines, music, protests, defacing, talks, typewriter art, and lots of creative spoils (see picture). My favourite stall was that of the inspiring Fine Cell Work, who work with prisoners to produce beautiful tapestry and embroidery work for sale. The arts cuts may have been devastating, but this expo showed that the spirit of artistic mischief is very much alive.

Labels:

100-word reviews,

events

Friday, 8 April 2011

100 Word Review - Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack

Posted by

Jon Stone

Surely if you're going to kick off a film with a series of barely-related scenes and events, you should at least tie them together with some atmospheric music? Not so GM&KG:GMA-OA (baddest acronym evah?), which spends far too long, even by Toho standards, following around some boring humans in their leisurely, tension-free attempts to predict the coming battle. As for the eventual showdown, Baragon's run-in with Godzilla gives us a refreshing change of scenery and lots of 'ouch!' moments, but the three-way clash between Mothra, King G and Godzilla is over-crowded with pyrotechnics, with Mothra once again turned to ash.

Labels:

100-word reviews,

film

Thursday, 7 April 2011

Early April General Update!

Posted by

Jon Stone

The next Sidekick Books release, Birdbook, should be arriving at our HQ in boxes tomorrow or Monday. Sorry it's taken so long but only two weeks ago, we were *still* discovering errors that had crept in between proofs (including, unfathomably, the replacement of a whole poem with another one - who is sabotaging us, and why?)

(EDIT - Birdbook now due next Friday (April 15th) as corrections need to be made to the spine)

This weekend's project: press releases!

The next issue of Fuselit, Contraption, is still badly delayed by a minor breakage of one of our computers. It's been to two repair shops already - one said they couldn't fix it while the other said it would cost £100 but they couldn't repair it *completely*. The manufacturers want proof of purchase if they're to repair it, which we've been unable to locate.

Why not just use the PC I'm typing on at the moment? Because it's new and doesn't like our old version of Quark. We're switching to InDesign but all the work we've done on the hard copy of Contraption is in Quark, which still runs off the broken laptop (when it's not broken).

Upshot: still hoping to finish it and have it out this month. Digital versions are more-or-less finished, but want to launch all three together. Fingers crossed! We will still aim to get two issues of Fuselit out this year so that we don't slip beyond the roughly biannual schedule.

Thanks, everyone, for your patience!

(EDIT - Birdbook now due next Friday (April 15th) as corrections need to be made to the spine)

This weekend's project: press releases!

The next issue of Fuselit, Contraption, is still badly delayed by a minor breakage of one of our computers. It's been to two repair shops already - one said they couldn't fix it while the other said it would cost £100 but they couldn't repair it *completely*. The manufacturers want proof of purchase if they're to repair it, which we've been unable to locate.

Why not just use the PC I'm typing on at the moment? Because it's new and doesn't like our old version of Quark. We're switching to InDesign but all the work we've done on the hard copy of Contraption is in Quark, which still runs off the broken laptop (when it's not broken).

Upshot: still hoping to finish it and have it out this month. Digital versions are more-or-less finished, but want to launch all three together. Fingers crossed! We will still aim to get two issues of Fuselit out this year so that we don't slip beyond the roughly biannual schedule.

Thanks, everyone, for your patience!

Labels:

fuselit news,

Sidekick Books

Unexpected item in the bagging area

Posted by

Mike

I think that what most disturbs me about supermarket self-checkout machines is that for most Anglicans, they have replaced Holy Communion as the primary routine liturgy. The self-checkout machine, like the communion rail, is to be approached meekly bending: the scanner traditionally operated in a half standing position, but at such a height that kneeling would be more feasible, were it socially acceptable.

The act of communion has always been a great leveller, both between churches and within them. The stripped pine, plain glass, jeans-and-jumpers evangelicals might turn their noses up at the incense and Gothic arches of the high church up the road; their aisles might even contain more people than candles; but even there, the chalice will be silver, not styrofoam, and nobody receives the Body and Blood of Christ sitting on a bean bag. In Sainsburys, your basket might contain quails' eggs and radicchio; mine a teetering balance of Quavers and Irn Bru; but we will get no unequal treatment from the touch sensitive screen.

Unlike the queue for the manned tills, the queue for the self-checkout machines is the place for last minute spiritual and mental reflection. Are my items in a fit state to pass before the scanner? Do I have any wayward loose vegetables that need to be accounted for on the special menu? Is my artisan loaf really what I think it is? because this, too, is a private test of honesty. The security guard won't notice if I enter a Poilâne as a Pain Rustique, but in the end, no spiritual shoplifter goes unprosecuted by the Good Shepherd. Yet as with the Blessed Sacrament, physical considerations intrude. Where is my vacant spot likely to open up? Which way will I turn to exit, and how can I do this while avoiding an embarrassing collision with those still waiting their turn?

In the busier establishments, we may be directed on our way by polite sidesmen: but when our time comes, each of us must stand, and scan, alone. Our hands and eyes move in union with the never-changing instructions, until the mystery of faith is transacted.

Please take your change

Amen

Please take your items

Amen

And it is in this season of Lent that the contrast stings the most. As we prepare for Easter, the aisle is dressed not with sackcloth but with Cadbury's Creme Eggs, already in their purples and golds. We are tempted as Christ would have been, had he spent his forty days and forty nights in the Goodge Street Tesco's.

Friday, 1 April 2011

100 Word Review - Half-Life 2 (XBox 360)

Posted by

Jon Stone

Alas, this hasn't aged very well. Back in the day, it was getting marks of 11 out of 10 and being cited as the greatest game ever. But whereas the original Half-Life remains a masterclass in spare and sure-footed narrative-driven gaming, its sequel is an awkward sprint from one infodump to the next. Characters stubbornly refuse to come to life and the now-not-that-impressive physics puzzles are somewhat crowbarred into frantic chase/escape scenes. The pacing is still strong and the multi-dimensional dystopia well realised, but it simply doesn't stand up to more recent games in the way true classics should.

Labels:

100-word reviews,

games

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)